Introducing mrva, a terminal-first approach to CodeQL multi-repo variant analysis

In 2023 GitHub introduced CodeQL multi-repository variant analysis (MRVA). This functionality lets you run queries across thousands of projects using pre-built databases and drastically reduces the time needed to find security bugs at scale. There’s just one problem: it’s largely built on VS Code and I’m a Vim user and a terminal junkie. That’s why I built mrva, a composable, terminal-first alternative that runs entirely on your machine and outputs results wherever stdout leads you.

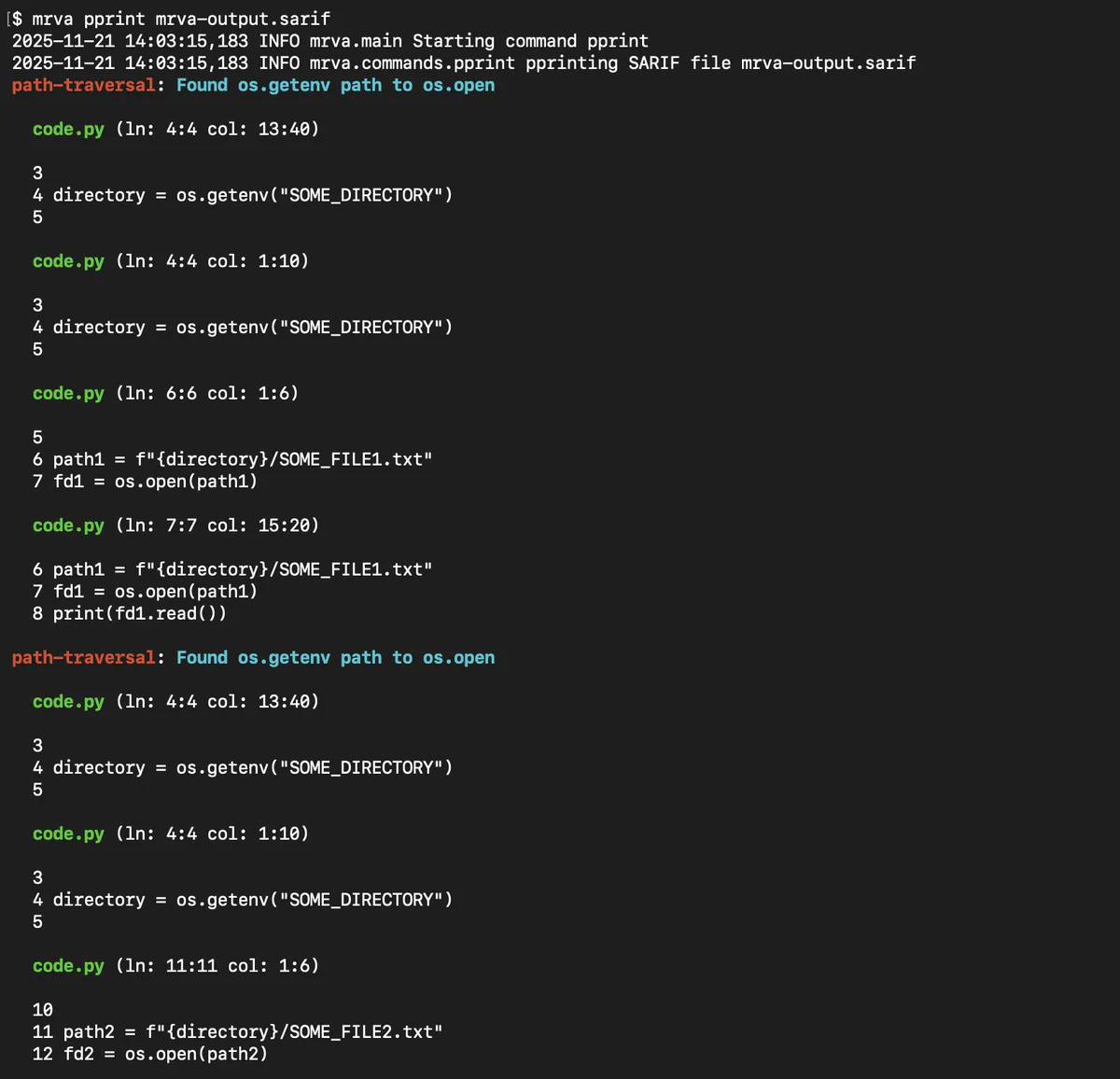

In this post I will cover installing and using mrva, compare its feature set to GitHub’s MRVA functionality, and discuss a few interesting implementation details I discovered while working on it. Here is a quick example of what you’ll see at the end of your mrva journey:

Installing and running mrva

First, install mrva from PyPI:

$ python -m pip install mrva

Or, use your favorite Python package installer like pipx or uv.

Running mrva can be broken down into roughly three steps:

- Download pre-built CodeQL databases from the GitHub API (

mrva download). - Analyze the databases with CodeQL queries or packs (

mrva analyze). - Output the results to the terminal (

mrva pprint).

Let’s run the tool with Trail of Bits’ public CodeQL queries. Start by downloading the top 1,000 Go project databases:

$ mkdir databases

$ mrva download --token YOUR_GH_PAT --language go databases/ top --limit 1000

2025-09-04 13:25:10,614 INFO mrva.main Starting command download

2025-09-04 13:25:14,798 INFO httpx HTTP Request: GET https://api.github.com/search/repositories?q=language%3Ago&sort=stars&order=desc&per_page=100 "HTTP/1.1 200 OK"

...You can also use the $GITHUB_TOKEN environment variable to more securely specify your personal access token. Additionally, there are other strategies for downloading CodeQL databases, such as by GitHub organization (download org) or a single repository (download repo). From here, let’s clone the queries and run the multi-repo variant analysis:

$ git clone https://github.com/trailofbits/codeql-queries.git

$ mrva analyze databases/ codeql-queries/go/src/crypto/ -- --rerun --threads=0

2025-09-04 14:03:03,765 INFO mrva.main Starting command analyze

2025-09-04 14:03:03,766 INFO mrva.commands.analyze Analyzing mrva directory created at 1757007357

2025-09-04 14:03:03,766 INFO mrva.commands.analyze Found 916 analyzable repositories, discarded 84

2025-09-04 14:03:03,766 INFO mrva.commands.analyze Running CodeQL analysis on mrva-go-ollama-ollama

...This analysis may take quite some time depending on your database corpus size, query count, query complexity, and machine hardware. You can filter the databases being analyzed by passing the --select or --ignore flag to analyze. Any flags passed after -- will be sent directly to the CodeQL binary. Note that, instead of having mrva parallelize multiple CodeQL analyses, we instead recommend passing --threads=0 and letting CodeQL handle parallelization. This helps avoid CPU thrashing between the parent and child processes. Once the analysis is done, you can print the results:

$ mrva pprint databases/

2025-09-05 10:01:34,630 INFO mrva.main Starting command pprint

2025-09-05 10:01:34,631 INFO mrva.commands.pprint pprinting mrva directory created at 1757007357

2025-09-05 10:01:34,631 INFO mrva.commands.pprint Found 916 analyzable repositories, discarded 84

tob/go/msg-not-hashed-sig-verify: Message must be hashed before signing/verifying operation

builtin/credential/aws/pkcs7/verify.go (ln: 156:156 col: 12:31)

https://github.com/hashicorp/vault/blob/main/builtin/credential/aws/pkcs7/verify.go#L156-L156

155 if maxHashLen := dsaKey.Q.BitLen() / 8; maxHashLen < len(signed) {

156 signed = signed[:maxHashLen]

157 }

builtin/credential/aws/pkcs7/verify.go (ln: 158:158 col: 25:31)

https://github.com/hashicorp/vault/blob/main/builtin/credential/aws/pkcs7/verify.go#L158-L158

157 }

158 if !dsa.Verify(dsaKey, signed, dsaSig.R, dsaSig.S) {

159 return errors.New("x509: DSA verification failure")

...This finding is a false positive because the message is indeed being truncated, but updating the query’s list of barriers is beyond the scope of this post. Like previous commands, pprint also takes a number of flags that can affect its output. Run it with --help to see what is available.

A quick side note: pprint is also capable of pretty-printing SARIF results from non-mrva CodeQL analyses. That is, it solves one of my first and biggest gripes with CodeQL: why can’t I get the output of database analyze in a human readable form? It’s especially useful if you run analyze with the --sarif-add-file-contents flag. Outputting CSV and SARIF is great for machines, but often I just want to see the results then and there in the terminal. mrva solves this problem.

Comparing mrva with GitHub tooling

mrva takes a lot of inspiration from GitHub’s CodeQL VS Code extension. GitHub also provides an unofficial CLI extension by the same name. However, as we’ll see, this extension replicates many of the same cloud-first workflows as the VS Code extension rather than running everything locally. Here is a summary of these three implementations:

mrva | gh-mrva | vscode-codeql | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Requires a GitHub controller repository | ❌ | ✅ | ✅ |

| Runs on GitHub Actions | ❌ | ✅ | ✅ |

| Supports self-hosted runners | ❌ | ✅ | ✅ |

| Runs on your local machine | ✅ | ❌ | ❌ |

| Easily modify CodeQL analysis parameters | ✅ | ❌ | ❌ |

| View findings locally | ✅ | ❌ | ✅ |

| AST viewer | ✅ | ❌ | ✅ |

| Use GitHub search to create target lists | ✅ | ❌ | ✅ |

| Custom target lists | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ |

| Export/download results | ✅ (SARIF) | ✅ (SARIF) | ✅ (Gist or Markdown) |

As you can see, the primary benefits of mrva are the ability to run analyses and view findings locally. This gives the user more control over analysis options and ownership of their findings data. Everything is just a file on disk—where you take it from there is up to you.

Interesting implementation details

After working on a new project I generally like to share a few interesting implementation details I learned along the way. This can help demystify a completed task, provide useful crumbs for others to go in a different direction, or simply highlight something unusual. There were three details I found particularly interesting while working on this project:

- The GitHub CodeQL database API

- Useful

database analyzeflags - Different kinds of CodeQL queries

CodeQL database API

Even though mrva runs its analyses locally, it depends heavily on GitHub’s pre-built CodeQL databases. Building CodeQL databases can be time consuming and error-prone, which is why it’s so great that GitHub provides this API. Many of the largest open-source repositories automatically build and provide a corresponding database. Whether your target repositories are public or private, configure code scanning to enable this functionality.

From Trail of Bits’ perspective, this is helpful when we’re on a client audit because we can easily download a single repository’s database (mrva download repo) or an entire GitHub organization’s (mrva download org). We can then run our custom CodeQL queries against these databases without having to waste time building them ourselves. This functionality is also useful for testing experimental queries against a large corpus of open-source code. Providing a CodeQL database API allows us to move faster and more accurately, and provides security researchers with a testing playground.

Analyze flags

While I was working on mrva, another group of features I found useful was the wide variety of flags that can be passed to database analyze, especially regarding SARIF output. One in particular stood out: --sarif-add-file-contents. This flag includes the file contents in the SARIF output so you can cross-reference a finding’s file location with the actual lines of code. This was critical for implementing the mrva pprint functionality and avoiding having to independently manage a source code checkout for code lookups.

Additionally, the --sarif-add-snippets flag provides two lines of context instead of the entire file. This can be beneficial if SARIF file size is a concern. Another useful flag in certain situations is --no-group-results. This flag provides one result per message instead of per unique location. It can be helpful when you’re trying to understand the number of results that coalesce on a single location or the different types of queries that may end up on a single line of code. This flag and others can be passed directly to CodeQL when running an mrva analysis by specifying it after double dashes like so:

$ mrva analyze <db_dir> <queries> -- --no-group-results ...CodeQL query kinds

When working with CodeQL, you will quickly find two common kinds of queries: alert queries (@kind problem) and path queries (@kind path-problem). Alert queries use basic select statements for querying code, like you might expect to see in a SQL query. Path queries are used for data flow or taint tracking analysis. Path results form a series of code locations that progress from source to sink and represent a path through the control flow or data flow graph. To that end, these two types of queries also have different representations in the SARIF output. For example, alert queries use a result’s location property, while path queries use the codeFlows property. Despite their infrequent usage, CodeQL also supports other kinds of queries.

You can also create diagnostic queries (@kind diagnostic) and summary queries (@kind metric). As their names suggest, these kinds of queries are helpful for producing telemetry and logging information. Perhaps the most interesting kind of query is graph queries (@kind graph). This kind of query is used in the printAST.ql functionality, which will output a code file’s abstract syntax tree (AST) when run alongside other queries. I’ve found this functionality to be invaluable when debugging my own custom queries. mrva currently has experimental support for printing AST information, and we have an issue for tracking improvements to this functionality.

I suspect there are many more interesting types of analyses that could be done with graph queries, and it’s something I’m excited to dig into in the future. For example, CodeQL can also output Directed Graph Markup Language (DGML) or Graphviz DOT language when running graph queries. This could provide a great way to visualize data flow or control flow graphs when examining code.

Running at scale, locally

As a Vim user with VS Code envy, I set out to build mrva to provide flexibility for those of us living in the terminal. I’m also in the fortunate position that Trail of Bits provides us with hefty laptops that can quickly chew through static analysis jobs, so running complex queries against thousands of projects is doable locally. A terminal-first approach also enables running headless and/or scheduled multi-repo variant analyses if you’d like to, for example, incorporate automated bug finding into your research. Finally, we often have sensitive data privacy needs that require us to run jobs locally and not send data to the cloud.

I’ve heard it said that writing CodeQL queries requires a PhD in program analysis. Now, I’m not a doctor, but there are times when I’m working on a query and it feels that way. However, CodeQL is one of those tools where the deeper you dig, the more you will find, almost to limitless depth. For this reason, I’ve really enjoyed learning more about CodeQL and I’m looking forward to going deeper in the future. Despite my apprehension toward VS Code, none of this would be possible without GitHub and Microsoft, so I appreciate their investment in this tooling. The CodeQL database API, rich standard library of queries, and, of course, the tool itself make all of this possible.

If you’d like to read more about our CodeQL work, then check out our CodeQL blog posts, public queries, and Testing Handbook chapter.

Contact us if you’re interested in custom CodeQL work for your project.