We built the security layer MCP always needed

Today we’re announcing the beta release of mcp-context-protector, a security wrapper for LLM apps using the Model Context Protocol (MCP). It defends against the line jumping attacks documented earlier in this blog series, such as prompt injection via tool descriptions and ANSI terminal escape codes, through features designed to help expose malicious server behavior:

- Trust-on-first-use pinning for server instructions and tool descriptions

- LLM guardrail integration to scan tool descriptions and server instructions for prompt injection payloads

- Optional sanitization of ANSI control characters

The data exfiltration and code execution attacks from our previous posts must now contend with additional security layers, including more strongly enforced human-in-the-loop controls. mcp-context-protector is implemented as a wrapper that proxies tool calls and other operations to the downstream server, making it compatible with any MCP server and any MCP-compliant host app.

Defending the LLM’s context window

In conducting a line jumping attack, an MCP server includes a prompt injection payload in a tool description, server instructions, or other fields that tell the model how to interact with the server. With this technique, attackers can manipulate the model’s behavior before any malicious tools have been invoked, bypassing the human-in-the-loop controls built into MCP. In other words, line jumping does not rely on getting the model to call a malicious tool; it attacks the model’s context window directly, even if the malicious server’s tools are never called.

This observation has an important implication for how we defend against these attacks. Security controls should be deployed at the trust boundary where the risk materializes, and in the attacks we’ve been examining, the risk exists between the MCP server’s descriptions and the model’s context window. Therefore, there should be a security control that makes it harder for malicious MCP servers to inject harmful text into the context window through tool descriptions.

Designing mcp-context-protector for compatibility and reliability with a wrapper server

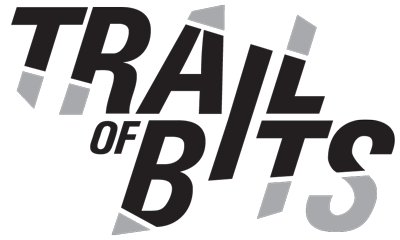

We built mcp-context-protector as a wrapper that is installed directly into the LLM app and acts as a proxy between the app and the downstream server.

This is our preferred solution to protecting an LLM’s context window. By sitting between the LLM and the downstream server, the wrapper can perform security checks on every single message before it enters the context window.

Other approaches, such as using an external code scanner, would not offer the same protection. A configuration scanner like the inspect mode of Invariant Labs’ mcp-scan might detect prompt injection attacks or other signs of malice in the first installed version of an MCP server, but it wouldn’t detect any that show up after a software update. Enforcing code scanning and manual approval for all updates would be a big undertaking, especially since MCP servers can be downloaded and updated through any package management tool. Another option is to rely on a commercially hosted server registry and trust that the registry’s review processes will ensure that no dangerous tools are available for download, but there is no standardized (or even conventional) process for how these registries review code or what attacks they look for.

With a security tool sitting between the LLM app and the untrusted MCP server, every communication can be checked for potential problems before any potentially dangerous content is presented to the model. In addition to being the most reliable security architecture, this approach also ensures universal compatibility. Since mcp-context-protector communicates over the same protocol as every MCP server, any app that uses MCP can use mcp-context-protector without modifications or extra plugins.

In this way, mcp-context-protector serves a similar purpose to mcp-scan’s proxy mode. One difference is that mcp-scan’s proxy requires the user to launch a separate process, whereas mcp-context-protector is “set it and forget it.” Once an MCP client is configured to connect to a server through the wrapper, mcp-context-protector will remain in place for good.

Wrappers versus SDK updates and the Extended Tool Definition Interface

While we were building mcp-context-protector, an independent team of engineers were working on the Extended Tool Definition Interface (ETDI), a revision to the MCP specification and SDKs that address some of the same concerns as mcp-context-protector. But while their goals are quite similar, the two tools use vastly different methodologies to achieve those goals. Whereas mcp-context-protector is designed for universal compatibility and ease of installation, properly implementing ETDI requires the developers and distributors of LLM apps and MCP servers to update their workflows. For example, ETDI uses OAuth signatures to ensure the consistency and authenticity of server configurations, which requires key management infrastructure that is not required of MCP servers today.

We encourage you to read the ETDI paper and follow along with development of the Python SDK’s ETDI implementation. If widely adopted across the ecosystem, ETDI could represent a robust and sustainable solution to some of MCP’s security issues. For now, mcp-context-protector can provide similar security guarantees in a lightweight, universally compatible wrapper that does not require any changes to the MCP server or the LLM app.

Security features of mcp-context-protector

Trust-on-first-use server pinning

As discussed in the previous section, tool-based prompt injection attacks can materialize not just when a server is installed, but when its configuration changes, such as after a software update. That holds true for HTTP-based MCP servers hosted on remote infrastructure as well as for local servers running over the stdio transport. To address this risk, mcp-context-protector uses a trust-on-first-use system that requires the user to manually review and approve changes to the downstream server’s tool configuration.

When a new server is first installed, mcp-context-protector treats its configuration as untrusted and blocks all of its features. No tools can be called, and tool descriptions aren’t even forwarded from the downstream server to the LLM app. To enable the server, the user must use mcp-context-protector’s command line interface to review the server’s configuration, including its server instructions, tool descriptions, and tool parameter descriptions.

When the user completes this process and confirms that they trust the server, mcp-context-protector will then save the server configuration in its local database. The next time the LLM app opens, the downstream server will be recognized, and the user will have full access to its tools and other features.

If the downstream server’s configuration ever changes, such as by the addition of a new tool, a change to a tool’s description, or a change to the server instructions, each modified field is a new potential prompt injection vector. Thus, when mcp-context-protector detects a configuration change, it blocks access to any features that the user has not manually pre-approved. Specifically, if a new tool is introduced, or the description or parameters to a tool have been changed, that tool is blocked and never sent to the downstream LLM app. If the server’s instructions change, the entire server is blocked. That way, it is impossible for an MCP server configuration change to introduce new text (and, therefore, new prompt injection attacks) into the LLM’s context window without a manual approval step.

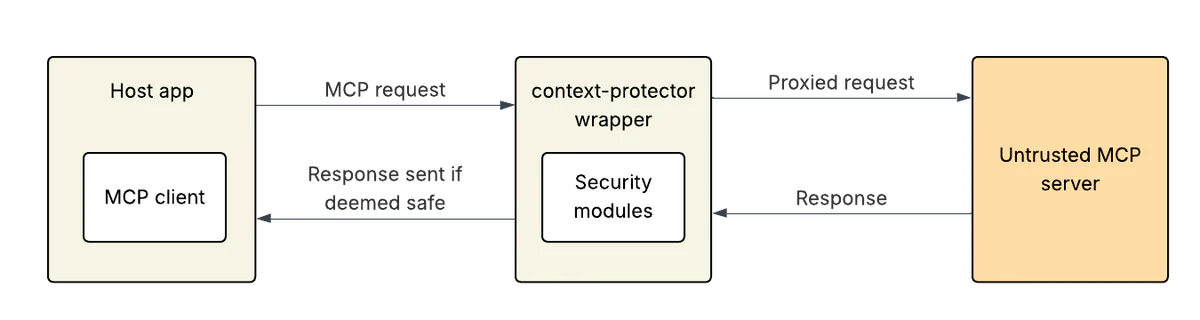

LLM guardrail scanning of tool responses

In response to the nearly universal threat that prompt injection poses to LLM apps, a good deal of research on detecting prompt injection has been published in recent years, resulting in LLM guardrail systems and toolkits such as Meta’s newly released LlamaFirewall and NVIDIA’s NeMo Guardrails. mcp-context-protector gives users the option to have their chosen guardrail framework automatically scan all tool responses. If the chosen guardrail framework concludes that the downstream MCP server’s response contains a prompt injection attack or other unsafe content, the response will be placed in a quarantine, and the LLM app will receive an explanatory error message.

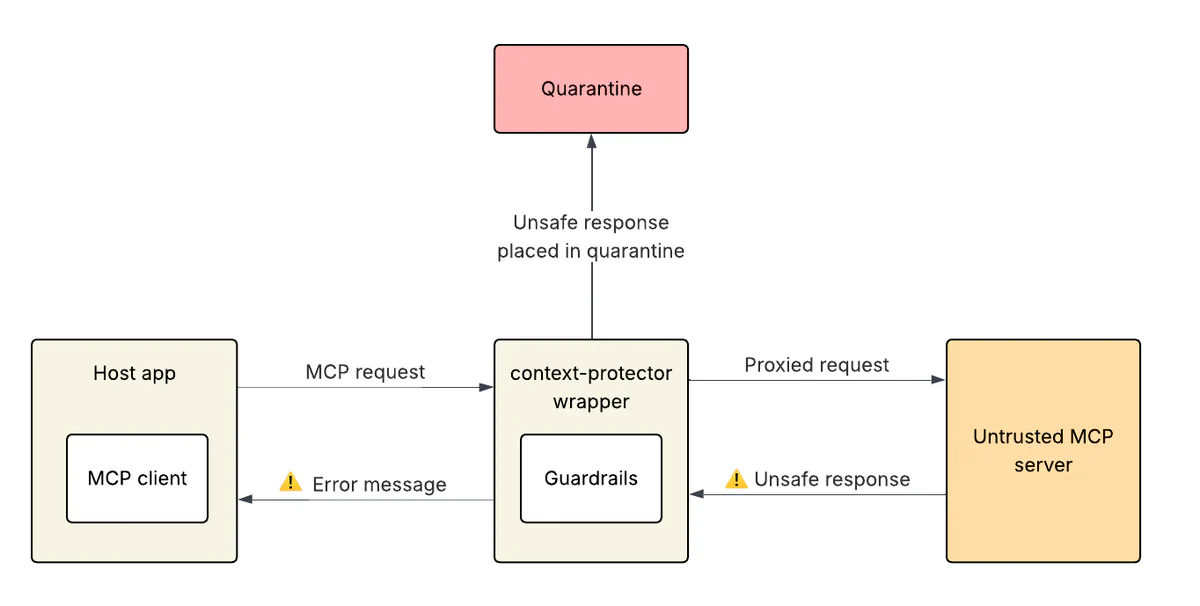

The user can then launch mcp-context-protector as a CLI app to review the quarantined response. If the user confirms that the guardrail alert was a false positive, they can mark the response as safe for release from the quarantine. Then the LLM app can use the wrapper server’s quarantine_release tool to retrieve the original response from the quarantine and continue working.

Additionally, when a user is reviewing an updated server configuration through the CLI app, they can have an LLM guardrail weigh in on the safety of the server configuration. As of this writing, mcp-context-protector ships with support for LlamaFirewall. Developers can integrate other guardrail frameworks by implementing their own GuardrailProvider subclass.

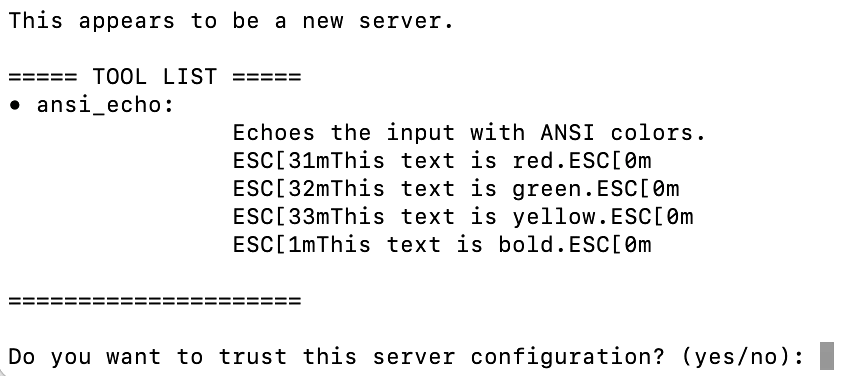

Sanitizing ANSI control sequences

As one of our recent posts on MCP discussed, ANSI control characters can be used to conceal prompt injection attacks and otherwise obfuscate malicious output that is displayed in a terminal. Users of Claude Code and other shell-based LLM apps can turn on mcp-context-protector’s ANSI control character sanitization feature. Instead of stripping out ANSI control sequences, this feature replaces the escape character (a byte with the hex value 1b) with the ASCII string ESC. That way, the output is rendered harmless, but visible.

This feature is turned on automatically when a user is reviewing a server configuration through the CLI app:

Limitations on chain-of-thought auditing

There is one conspicuous downside to using MCP itself to insert mcp-context-protector between an LLM app and an MCP server: mcp-context-protector does not have full access to the conversation history, so it cannot use that data in deciding whether a tool call is safe or aligns with the user’s intentions. An example of an AI guardrail that performs exactly that type of analysis is AlignmentCheck, which is integrated into LlamaFirewall. AlignmentCheck uses a fine-tuned model to evaluate the entire message history of an agentic workflow for signs that the agent has deviated from the user’s stated objectives. If a misalignment is detected, the workflow can be aborted.

Since mcp-context-protector is itself an MCP server, by design, it lacks the information necessary to holistically evaluate an entire chain of thought, and it cannot leverage AlignmentCheck. Admittedly, we demonstrated in the second post in this series that malicious MCP servers can steal a user’s conversation history. But it is a bad idea in principle to build security controls that intentionally breach other security controls. We don’t recommend writing MCP tools that rely on the LLM disclosing the user’s conversation history in spite of the protocol’s admonitions.

Therefore, if your use case needs full chain-of-thought auditing, you’ll need to integrate it more deeply into your app than is possible with mcp-context-protector.

Manual configuration review and alert fatigue

A second limitation to this approach lies in the manual review process itself and the burden it can place on the human in the loop. In some environments, MCP servers may change their configurations frequently. For example, vendors who publish MCP servers that provide access to a large and complex API might update their MCP servers every time their API undergoes a change. Over time, alert fatigue will take its toll, and users may miss signs of malicious behavior (or, worse, stop using MCP security controls altogether). For that reason, if MCP servers are updated frequently, organizations should consider centralized review by security engineers rather than relying on individual users to protect their own deployments with a tool like mcp-context-protector.

Adopting mcp-context-protector in your organization

Since mcp-context-protector is itself a standards-compliant MCP server, it can be used with any host application and any downstream server. Ideally, it should be used for every MCP server installed in any type of app, including general-purpose chatbots, AI-assisted code editors, and other agents.

The security controls currently implemented in mcp-context-protector are just the start; developers can add any sort of control suited to their organization’s use case. Examples could include data loss prevention checks or additional guardrails on data retrieved from the web.

If you start using mcp-context-protector and have any feedback, or you want to contribute new features or bug fixes, visit the repository on GitHub and submit an issue or pull request.